"Order cheap diclofenac online, arthritis in sides of feet".

By: J. Bengerd, M.A., M.D., M.P.H.

Medical Instructor, University of New Mexico School of Medicine

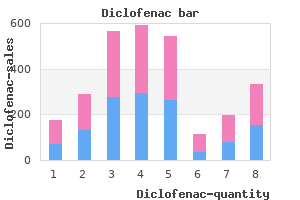

Caterpillars of the native large blue butterfly (Maculina arion) in Great Britain required development in underground nests of the native ant Myrmica sabuleti treating arthritis of the thumb order diclofenac without a prescription. The ant avoids nesting in overgrown areas rheumatoid arthritis eczema 50mg diclofenac free shipping, which for centuries had not been problematic because of grazing and cultivation. However, changing land use patterns and decreased grazing led to a situation in which rabbits were the main species maintaining suitable habitat for the ant. When the virus devastated rabbit populations, ant populations declined to the extent that the large blue butterfly was extirpated from Great Britain (Ratcliffe 1979). In another striking chain reaction, landlocked kokanee salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka), were introduced to Flathead Lake, Montana in 1916, replacing most native cutthroat trout (O. The kokanee were so successful that they spread far from the lake, and their spawning populations became so large that they attracted large populations of bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), grizzly bears (Ursus arctos horribilis), and other predators. Between 1968 and 1975, opossum shrimp (Mysis relicta), native to large deep lakes elsewhere in North America and in Sweden, were introduced to three lakes in the © Oxford University Press 2010. However, the kokanee also fed on these prey, and kokanee populations fell rapidly, in turn causing a precipitous decline in local bald eagle and grizzly bear numbers (Spencer et al. Bithynia also vectors this species, which has turned out also to be lethal to ducks (Cole and Friend 1999). So in this instance, the introduced snail and the introduced trematode combine to produce more mortality in ducks than either would likely have accomplished alone. Sometimes introduced animals either pollinate introduced plants or disperse their seeds. That situation changed abruptly upon the arrival of the figwasps of three of the fig species, which now produce seeds. On the island of La Rйunion, the red-whiskered bulbul (Pycnonotus jocosus), introduced from Asia via Mauritius, disperses seeds of several invasive introduced plants, including Rubus alceifolius, Cordia interruptus, and Ligustrum robustrum, which have become far more problematic since the arrival of the bulbul (Baret et al. The Asian common myna (Acridotheres tristis) was introduced to the Hawaiian islands as a biological phytoplankton cladoceran opossum shrimp copepod McDonald Creek kokanee salmon lake trout Flathead Lake Figure 7. Also in Hawaii, introduced pigs selectively eat and thereby disperse several invasive introduced plant species, and by rooting and defecating they also spread populations of several introduced invertebrates, while themselves fattening up on introduced, protein-rich European earthworms (Stone 1985). Habitat modification by introduced plants can lead to a meltdown process with expanded and/ or accelerated impacts. As noted above, the nitrogen-fixing Morella faya (firetree) from the Azores has invaded nitrogen-deficient volcanic regions of the Hawaiian Islands. Because there are no native nitrogen-fixing plants, firetree is essentially fertilizing large areas. Many introduced plants established elsewhere in Hawaii had been unable to colonize these previously nutrient-deficient areas, but their invasion is now facilitated by the activities of firetree (Vitousek 1986). In addition, firetree fosters increased populations of introduced earthworms, and the worms increase the rate of nitrogen burial from firetree litter, thus enhancing the effect of firetree on the nitrogen cycle (Aplet 1990). Finally, introduced pigs and an introduced songbird (the Japanese white-eye, Zosterops japonicus) disperse the seeds of the firetree (Stone and Taylor 1984, Woodward et al. In short, all these introduced species create a complex juggernaut of species whose joint interactions are leading to the replacement of native vegetation. Large, congregating ungulates can interact with introduced plants, pathogens, and even other animals in dramatic cases of invasional meltdown. For instance, Eurasian hooved livestock devastated native tussock grasses in North American prairie regions but favored Eurasian turfgrasses that had coevolved with such animals and that now dominate large areas (Crosby 1986). In northeastern Australia, the Asian water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis), introduced as a beast of burden and for meat, damaged native plant communities and eroded stream banks. The Central American shrub Mimosa pigra had been an innocuous minor component of the vegetation in the vicinity of the town of Darwin, but the water buffalo, opening up the flood plains, created perfect germination sites of Mimosa seedlings, and in many areas native sedgelands became virtual monocultures of M. The mimosa in turn aided the water buffalo by protecting them from aerial hunters (Simberloff and Von Holle 1999). In North America, the introduced zebra mussel filters prodigious amounts of water, and the resulting increase in water clarity favors certain plants, including the highly invasive Eurasian watermilfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum). The milfoil then aids the mussel by providing a settling surface and facilitates the movement of the mussel to new water bodies when fragments of the plant are inadvertently transported on boat propellers or in water (Simberloff and Von Holle 1999). Some instances of invasional meltdown arise when one introduced species is later reunited with a coevolved species through the subsequent introduction of the latter. The fig species and their pollinating fig wasps in Florida are an example; the coevolved mutualism between the wasps and the figs is critical to the impact of the fig invasion. The water buffalo from Asia and Mimosa pigra from Central America could not have coevolved, nor could the Asian myna and the New World Lantana camara in Hawaii.

Since IgG antibody is often present in quantities greatly exceeding the quantity of IgE antibody arthritis in neck bone spurs purchase diclofenac pills in toronto, specific IgG antibody may bind to available sites of the allergosorbent arthritis diet control discount 75 mg diclofenac free shipping, thereby preventing subsequent IgE binding and leading potentially to falsely low or negative test results. In this case, a patient who is sensitized to an allergen may have a positive test result to both the original allergen and other allergens that cross-react with the original allergen. Exposure to cross-reactive allergens may or may not provoke symptoms (eg, most grass-sensitive patients tolerate wheat, a potent cross-reactant in grass pollen extracts). This problem of allergen cross-reactivity may also complicate interpretation of skin tests. As with skin testing, IgE antibody specificities involving extracts that contain potent allergenic components such as ragweed, house dust mite, and cat epidermals tend to correlate much better with clinical sensitivity and provocation tests. This situation may be compounded further in the case of foods in which multiple allergenic epitopes are often contained in the crude extract mixture and minor components may actually dilute the major allergen responsible for clinical sensitization. Furthermore, as discussed herein, certain allergenic epitopes in foods (ie, wheat) may strongly cross-react with allergens in 1 of the potent classes of inhalant aeroallergens (ie, grass), leading to spuriously false-positive results. However, the predictive value of anaphylactogenic food specific IgE for outcome of oral food challenge has received considerable attention and is discussed below and further in part 2. Inhibition of Specific IgE Antibody Binding the most expedient method for determining the specificity of IgE binding is to determine whether the addition of a small quantity of a homologous allergen in the fluid phase will inhibit most IgE binding. Inhibition usually indicates that IgE binding in the assay is a result of the IgE antibody specifically recognizing the allergenic protein. If IgE is being nonspecifically bound, either most serum samples are positive in the assay or there is a relationship between the total serum IgE concentration and an increase of assay positivity to multiple lectin-containing allergens. In demonstrating specific inhibition, it should be possible to inhibit at least 80% of the specific IgE binding in a dose response manner. When the quantity of specific IgE is kept constant, the percentage of inhibition produced can be used to estimate the quantity of allergen in the fluid phase. Under appropriate experimental conditions, including an adequate supply of potent allergen specific IgE, inhibition can be used to standardize allergen extracts, estimate the quantities of allergens, and evaluate cross-reactivity between allergens. IgG and IgG subclass antibody tests for food allergy do not have clinical relevance, are not validated, lack sufficient quality control, and should not be performed. Although a number of investigators have reported modest increases of IgG4 during venom immunotherapy, confirmation and validation of the predictive value of IgG4 for therapeutic efficacy of venom immunotherapy are not yet proven. The antibody used to measure the IgG bound in an assay can be either an anti-human IgG or specific for 1 of the subclasses of IgG (IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, or IgG4). When subclass specific IgG antibodies are used, the quantity of the particular IgG antibody subclass can be determined. IgG and IgG subclass antibodies specific for allergens usually are measured in arbitrary units, although mass values may be extrapolated from a total or subclass specific standard curve. An allergen specific IgG assay is subject to the same technical problems as specific IgE assays, and specific IgG assays should be evaluated using the same criteria and techniques as those used for IgE assays. The level of expected precision should be 2 significant figures with variation less than 15%, or lower, since the quantity of IgG to be measured is often relatively large, especially after immunotherapy. Measurements of total serum IgE concentration are of modest clinical value when used as a screen for allergic disease or for predicting the risk of allergic disease. There is also a suggestion that the serum IgE concentration is an indicator of disease activity and that serial determinations should be used to evaluate the adequacy of treatment. After 1 month of taking omalizumab, a new assay that measures the level of circulating IgE that is free or unbound with omalizumab can confirm the effectiveness of the dosing regimen. Since the course of IgE myeloma is distinct from that of light chain disease and other myelomas, IgE should be measured in patients with clinical symptoms suggestive of myeloma and in whom myelomas of other isotypes have been ruled out. In drug-induced interstitial nephritis or graft vs host disease, there may be a relationship among the course of the disease, response to therapy, and the IgE level, but none of these relationships are firm enough to recommend total IgE as part of the clinical evaluation of these diseases. Based on current information, there is no clinical indication for attempting to measure allergen specific IgE in cord blood. However, several investigations have shown that elevated food specific IgE in early infancy may predict respiratory sensitization at a later age. Prototypic, miniaturized, multiarray assays may offer a similar advantage in the future. If the multiple allergen test result is positive, there is a high probability that the patient is allergic to at least 1 of the allergens included in the test. Additional tests that use individual allergens then can be used to determine other allergens to which the patient may be sensitive. In general, these multiallergen screening tests have shown acceptable diagnostic sensitivity and specificity when compared with skin tests.

Generic 50mg diclofenac free shipping. Rheumatoid Arthritis: Infusion Therapy Brings New Hope.

These forests grow in a relatively high rainfall environment (>1100 mm per annum) with a limited summer drought of less than three months duration what does arthritis in your neck feel like purchase diclofenac with amex. Elsewhere in Australia rheumatoid arthritis fingers purchase diclofenac now, such a climate would support rainforest if protected from fire. However, in southwestern Australia there are no continuously regenerating and fire intolerant rainforest species to compete with karri, although geological and biogeographic evidence point to the existence of rainforest in the distant past. The cause of this disappearance appears to be Tertiary aridification and the accompanying increased occurrence of landscape fire. Such convergence suggests that all have been exposed to similar natural selection pressures and have evolved to compete with rainforest species by using fire as an agent of interspecific competition. The extraordinary diversity of the genus Eucalyptus and convergent evolution of traits such as gigantism in different lineages in this clade, and similar patterns of diversification in numerous other taxonomic groups, leads to the inescapable conclusion that fire had been an integral part of the Australian environment for millions of years before human colonization. An Upper Pliocene lacustrine environmental record from southWestern Australia-preliminary results. The lifecycle of these trees depends upon infrequent fire to enable seedling establishment. Without fire a dense temperate Nothofagus rainforest develops because of the higher tolerance of rainforest seedlings to low light conditions. Even within fire-prone landscapes, there may be species and indeed whole communities that are fire-sensitive. Typically these occur in parts of the landscape where fire frequency or severity is low, possibly due to topographic protection. For example, when fire sensitive rainforest communities occur within a flammable matrix of grassland and savanna, as throughout much of the tropics, they are often associated with rocky gorges, incised gullies (often called "gallery for- ests"), and slopes on the lee-side of "fire-bearing" winds (Bowman 2000). Several factors lead to this association: fires burn more intensely up hill, especially if driven by wind; rocks tend to limit the amount of grassy fuel that can accumulate; deep gorges are more humid, reducing the flammability of fuels; and high soil moisture may lead to higher growth rates of the canopy trees, increasing their chances of reaching maturity, or a fireresistant size, between fires. Such fires greatly reduce fuel loads and thus the likelihood of large, intense fires. In addition, because low intensity fires are typically more patchy than high intensity fires, they tend to leave populations of fire-sensitive species undamaged providing a seed source for regeneration. Such an example is provided by the decline of the fire-sensitive endemic Tasmanian conifer King Billy pine (Athrotaxis selaginoides) following the cessation of Aboriginal landscape burning (Brown 1988; http:/ / The relatively high frequency of low-intensity fires under the Aboriginal regime appears to have limited the occurrence of spatially extensive, high intensity fires. Under the European regime, no deliberate burning took place, so that when wildfires inevitably occurred, often started by lightning, they were large, intense, and rapidly destroyed vast tracts of King Billy pine. Over the last century, about 30% of the total coverage of King Billy pine has been lost. A similar situation has resulted in the decline of the cypress pine (Callitris intratropica) in northern Australian savannas (Bowman and Panton 1993). Mature trees have thick bark and can survive mild but not intense fires, and if stems are killed it has very limited vegetative recovery. Populations of cypress pine can survive mild fires occurring every 28 years, but not frequent or more intense fires because of the delay in seedlings reaching maturity and the cumulative damage of fires to adults. Cessation of Aboriginal land management has led to a decline of cypress pine in much of its former range, and it currently persists only in rainforest margins and savanna micro-sites such as in rocky crevasses or among boulders or drainage lines that protect seedlings from fire (Figure 9. Fire sensitive species such as King Billy pine and cypress pine are powerful bio-indicators of altered fire regimes because changes in their distribution, Figure 9. Changes in fire regime following the breakdown of traditional Aboriginal fire management have seen a population crash of this species throughout its range in northern Australia. Such habitat complexity provides a diversity of microclimates, resources, and shelter from predators. It is widely believed that the catastrophic decline of mammal species in central Australia, where clearing of native vegetation for agriculture has not occurred, is a direct consequence of the homogenization of fine-scale habitat mosaics created by Aboriginal landscape burning. This interpretation has been supported by analysis of "fire scars" from historical aerial photography and satellite imagery. In 1953, the study area contained 372 fire scars with a mean area of 34 ha, while in 1986, the same area contained a single fire scar, covering an area of 32 000 ha. Clearly, the present regime of large, intense and infrequent fires associated with lightning strikes has obliterated the fine-grained mosaic of burnt patches of varying ages that Aboriginal people had once maintained (Burrows et al. The cessation of Aboriginal landscape burning in central Australia has been linked to the range contraction of some mammals such as the rufous hare-wallaby (Lagorchestes hirsutus) (Lundie-jenkins 1993).

Ideally arthritis in the knee exercise program cheap diclofenac 75 mg visa, samples should be unrelated and representative of the populations under investigation arthritis in neck and shoulders buy genuine diclofenac online. Generally, the sampling of 30 to 50 well-chosen individuals per breed is considered sufficient to provide a first clue as to breed distinctiveness and within-breed diversity, if a sufficient number of independent markers is assayed. However, the actual numbers required may vary from case to case, and may be even lower in the case of a highly inbred local population, and higher in a widely spread population divided into different ecotypes. The choice of unrelated samples is quite straightforward in a well-defined breed, where it can be based on the herd book or pedigree record. Conversely, it can be rather difficult in a semi-feral population for which no written record is available. The record of geographical coordinates, and photo-documentation of sampling sites, animals and flocks is extremely valuable to check for cross-breeding in the case of unexpected outliers, or for identifying interesting geographic patterns of genetic diversity. A well-chosen set of samples is a long-lasting valuable resource, which can be used to produce meaningful results even with poor technology. Conversely, a biased sample will produce results that are distorted or difficult to understand even if the most advanced molecular tools are applied. Microsatellite data are also commonly used to assess genetic relationships between populations and individuals through the estimation of genetic distances. Genetic relationship between breeds is often visualized through the reconstruction of a phylogeny, most often using the neighbourjoining (N-J) method (Saitou and Nei, 1987). However, a major drawback of phylogenetic tree reconstruction is that the evolution of lineages is assumed to be non-reticulate, i. This assumption will rarely hold for livestock, where new breeds often originate from cross-breeding between two or more ancestral breeds. The visualization of the evolution of breeds provided by phylogenetic reconstruction must, therefore, be interpreted cautiously. Multivariate analysis, and more recently Bayesian clustering approaches, have been suggested for admixture analysis of microsatellite data from different populations (Pritchard et al. Probably the most comprehensive study of this type in livestock is a continent-wide study of African cattle (Hanotte et al. Molecular genetic data, in conjunction with, and complemented by, other sources such as archaeological evidence and written records, provide useful information on the origins and subsequent movements and developments of genetic diversity in livestock species. Mapping the origin of current genetic diversity potentially allows inferences to be made about where functional genetic variation might be found within a species for which only limited data on phenotypic variation exist. Combined analysis of microsatellite data obtained in separate studies is highly desirable, but has rarely been possible. The application of different microsatellite genotyping systems causes variation between studies in the estimated size of alleles at the same loci. There are only a few examples of large-scale analyses of the genetic diversity of livestock species. Ongoing close coordination between large-scale projects promises the delivery of a global estimate of genetic diversity in the near future for some species such as sheep and goats. In the meantime, new methods of data analysis are being developed to permit the meta-analysis of datasets that have only a few breeds and no, or only a few, markers in common (Freeman et al. This global perspective on livestock diversity will be extremely valuable to reconstruct the origin and history of domestic animal populations and, indirectly, of human populations. It will also highlight regional and local hotspots of genetic diversity which may be targeted by conservation efforts. This is likely, in the near future, to permit the parallel analysis of a large number of markers at a lower cost. With this perspective, large-scale projects are ongoing in several livestock species to identify millions. When data have not been obtained randomly, standard estimators of population genetic parameters cannot be applied. For example, the Middle Eastern origin of modern European cattle was recently demonstrated by Troy et al. The study identified four maternal lineages in Bos taurus and also demonstrated the loss of bovine genetic variability during the human Neolithic migration out of the Fertile Crescent.

It should be noted that regardless of the logistic constraints rheumatoid arthritis and lupus cheap 50mg diclofenac otc, biological consideration and statistical minutiae driving the choice of a particular set of metrics for biodiversity arthritis in small breed dogs order diclofenac pills in toronto, one must not forget to consider the cost-benefit ratio of any selected method (Box 16. Gardner There is a shortage of biological data with which to meet some of the primary challenges facing conservation, including the design of effective protected area systems and the development of responsible approaches to managing agricultural and forestry landscapes. This data shortage is caused by chronic underfunding of conservation science, especially in the species rich tropics (Balmford and Whitten 2003), and the high financial cost and logistical difficulties of multitaxa field studies. We must therefore be judicious in identifying the most appropriate species groups for addressing a particular objective. This failing threatens to erode the credibility of conservation science to funding bodies and policy makers. To maximize the utility of biodiversity monitoring, it should adhere to the concepts of return on investment, and value for money. In essence this means that fieldworkers need to plan around two main criteria in selecting which species to sample: (i) what types of data are needed to tackle the objective in hand; and (ii) feasibility of sampling different candidate species groups. Practical considerations should include the financial cost of surveying, but also the time and expertise needed to conduct a satisfactory job. The objective of that study was to provide representative and reliable information on the ecological consequences of converting tropical rainforest to Eucalyptus plantations or fallow secondary regeneration. An audit was conducted of the cost (in money and time) of sampling 14 groups of animals (vertebrates and invertebrates) across a large, managed, lowland forest landscape. Notably, survey costs varied by three orders of magnitude and comparing standardised costs with the indicator value of each taxonomic group clearly demonstrated that birds and dung beetles (Coleoptera: Scarabaeinae) are highperformance groups they provide the most amount of valuable information for the least cost. By contrast, other groups like small mammals and large moths required a large investment for little return (see Box 16. The fact that both birds and dung beetles are wellstudied and perform important ecological functions gives further support to their value for biodiversity monitoring and evaluation. This important finding will help conservation biologists in prioritising the study of the effects of deforestation on landuse change in the Amazon, allowing them to design costeffective field expeditions that will deliver the most useful information for the money available. Finally when planning biodiversity surveys it is also important to consider how the data may be used to address ancillary objectives that may ensure an even greater return on investment. One example is the opportunity to synthesise information from many smallscale monitoring programs to provide robust nationwide assessments of the status of biodiversity without needing to implement independent studies. A better understanding of the distribution of species in threatened ecosystems will improve our ability to safeguard the future of biodiversity. We cannot afford to waste the limited resources we have available to achieve this fundamental task. Indicator performance (% indicator species of total) 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 0 Small mammals Moths Birds Dung beetles 2000 4000 6000 Standardised sampling cost ($) 8000 Box 16. Without proper thoughtfulness, openness, flexibility, and (most importantly) humour, these projects fail for reasons that are often difficult to distil. All conservation projects involve a mix of stakeholders (local people, scientists, conservation practitioners, governmental and public administrators, educators, community leaders, etc. Having worked on both successful and failed projects with a diversity of people in nine countries and six languages, much of what I have learned can be summed up in two simple yet powerful ideas for all stakeholders: clear communication and equity. No matter the socio cultural context, a common denominator of transparency is necessary for a successful conservation project. Having stakeholders explicitly state their intentions, desires and goals is a good start. It also helps elicit traditional or anecdotal knowledge that can be useful in formal analysis. A common pitfall is an inability for leaders to communicate effectively (for many and sundry reasons), reenforcing topdown stereotypes. Lateral communication (peertopeer) can be more effective and avoids many constraints imposed by translating among different languages or cultures, effectively levelling the playing field and enabling everyone to participate (at least for heuristic purposes). Activities that enhance transparent communication include small group discussions, workshops, regular and frequent meetings, project site visits and even informal gatherings such as shared meals or recreational activities. Almost all social hierarchies involve some component of conflict based around inequity. Conservation projects should, wherever possible, bridge gaps and narrow divides by developing equitably among stakeholders. By alleviating large disparities in cost:benefit ratios, responsibilities, and expectations between different stakeholders, the project will become more efficient because there will be less conflict based on inequity. Equity will evolve and change, with stakeholders adapting to behave fairly in a transparent system.

Additional information: