Judiciary is our most trusted and valued institution. However, the mechanisms for judicial appointments have proved to be inadequate in elevating the best and the brightest to the Bench. Also, the existing arrangements to hold erring judges to account have failed.

Click on the image the view the infographic on Judicial Reforms

Recent Efforts |

| The Supreme Court of India has struck down the 99th Constitutional Amendment, which provided for the National Judicial Appointments Commission for the appointment of Judges to the Supreme Court and High Courts. Prior to the verdict, FDR had initiated a mammoth exercise of providing the background material in support of NJAC to all Members of the Parliament urging them to set aside their partisan and political differences and stand united on this vital issue to protect the integrity of the Constitution, supremacy of Parliament and democratic legitimacy of all institutions. Read here the letter written by Dr. Jayaprakash Narayan to all parliamentarians and the enclosed background material supporting NJAC. |

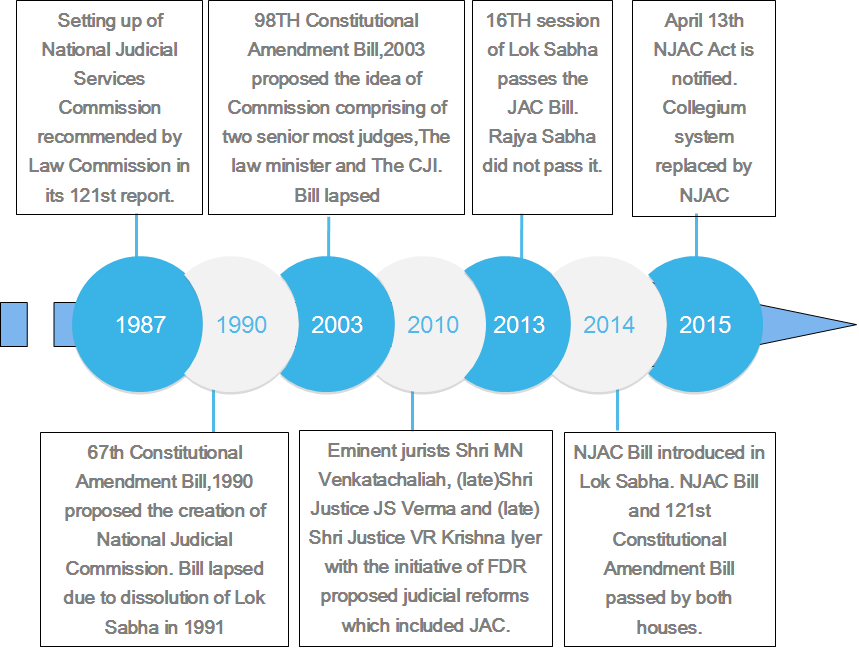

Judicial Appointments Commission

In light of the need for Judicial Reforms in India, FDR / Lok Satta in consultation with three eminent jurists – Shri Justice M N Venkatachaliah, (late) Shri Justice J S Verma and (late) Shri Justice V R Krishna Iyer had proposed various recommendations for Judicial Reforms including the creation of an All India Judicial Service (AIJS) and National Judicial Commission (NJC) towards ensuring quality and excellence in subordinate judiciary and enhancing accountability in the higher judiciary, respectively.

FDR / Lok Satta has maintained that usurpation of the power to appoint judges by the Supreme Court is plainly unconstitutional, and violates the principle of checks and balance in relation to organs of the State. This system has been found to be unsatisfactory and undermining the quality and credibility of the judiciary.

Thus, National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) Act, 2014 and The Constitution (Ninety-Ninth Amendment) Act, 2014 which seek to enable equal participation of Judiciary and Executive, make the appointment process more accountable and ensure greater transparency and objectivity in the appointments to the higher judiciary and do away with the present system, is a good step.

Similarly, the Judicial Standards and Accountability Bill, 2013 which seeks to create a permanent and credible mechanism to inquire into complaints against judges, as well as create other mechanisms of judicial accountability has lapsed with the dissolution of 15th Lok Sabha.

Creation of All-India Judicial Service (AIJS)

The competence and quality of judges in trial courts is critical for the integrity and credibility of the whole justice system. Therefore there is a strong case for creation of an All-India Judicial Service, in line with the IAS and IPS. FDR/Lok Satta in 2010 urged three eminent jurists – Sri Justice MN Venkatachaliah, (late) Sri Justice JS Verma, and (late) Sri Justice VR Krishna Iyer – to examine the issue of creation of an Indian Judicial Service. They gave their joint view as follows:

“We agree with the urgent need to constitute the All India Judicial Service envisaged by Article 312 of the Constitution of India, at par with the other All India services like the I.A.S. to attract the best available talent at the threshold for the subordinate judiciary, which is at the cutting edge of the justice delivery system to improve its quality. Moreover, the subordinate judiciary is important feeder-line for appointments to the High Court. The general reluctance of competent lawyers to join the Bench even at the higher levels adds an additional urgency to the problem. AIJS will, in due course of time, also help to improve the quality of the High Courts.

The modalities for creating the AIJS to achieve its avowed purpose, and the necessary constitutional changes and the legal frame-work can be worked out after acceptance of the proposal in principle.”

Article 312 of the Constitution provides for the creation of an All–India Judicial Service (AIJS) common to the Union and the States. Such a service can be created and regulated by the Parliament by law, provided that the Council of States has declared by resolution supported by not less than two-thirds of the members present and voting that it is necessary or expedient in the national interest to do so.

Speedy implementation of The Gramnyayalayas Act, 2008

The Government through the President’s address to Parliament gave a commitment to make dispensation of justice simpler, quicker and more effective, and to double the number of courts and judges in the subordinate judiciary in a phased manner. The government also announced its commitment to a policy of zero tolerance for violence against women, and to strengthen the criminal justice system for its effective implementation.

As a result of FDR/Lok Satta’s efforts towards speedy, accessible and affordable justice the Parliament has enacted the Gram Nyayalayas Act in 2008 (Act 4 of 2009), providing for rural local courts for speedy justice through summary procedure, as an integral part of independent justice system. Under this law local courts should be appointed at intermediate Panchayat level. One of the problems of our justice system is many simple cases – civil or criminal – do not even reach the courts because of inaccessibility, cost and delays. Often people suffer injustice silently, or resort to rough and ready justice through extra-legal, often violent means. Local Courts with summary procedures can provide speedy relief and justice in many simple cases at a low cost.

However, as of December 2013, only 172 Gram Nyayalayas have been notified in nine states, only 152 have been functional. There is urgent need to create these local courts. Even at one local court per block, we can create 5000 courts at a low-cost in rural areas.

In addition, there is increasing petty crime in urban areas, including harassment of women and eve-teasing. Growing urbanization and impersonal lives are eroding social and family controls. Young men who behave obediently at home often become a menace to women in public places. Daily harassment, eve teasing, inappropriate remarks, touching without permission in public transport vehicles – all these have become increasingly common. For women to be safe it is not enough to impose severe punishment for serious sexual offences; we need to create a culture and climate of complete safety from daily taunts and humiliation. When routine daily insults and humiliation are unchecked, serious crime against women becomes much more likely.

By expanding local courts all over the country, especially in urban areas, we can create an acceptable, simple mechanism for ensuring speedy justice in cases of ill-treatment of women, as well as many simple civil and criminal cases. Also for simple offences of eve-teasing and harassment, swift punishment and assured follow up will have great deterrent effect. For instance, if a person is held guilty of eve-teasing or harassment in a bus or train, the trial in a local court can be completed within days, and the person, in case of first offence can be imposed a fine and the conviction can be entered in his academic and employment record, with the condition that the entries can be deleted by the court after three years of good conduct. A second minor offence can lead to a month’s jail term, rustication from college and a permanent entry of conviction in his records. Such swift and sure action with follow up will create a culture of zero tolerance of all forms of harassment of women, ensuring women’s safety and dignity in public places.Provisions may be made in the criminal law for providing for summary trial and speedy justice in local courts in all minor cases of sexual harassment like eve-teasing, harassment etc..,